Leland,

she was yours

by accident of birth.

But your stunted love

sprouted to garish green jealousy.

Control was all.

Sully her

so she’s no good for anyone.

Then consort with Bob

to kill her for what she’s become.

May you char on a slowly-turned spit,

and heal each day anew,

in Hell.

Category Archives: fiction

Harvey and the flying machine

Ahhh..I am so tired. But, a story I will tell you, for your little ones.

Harvey, of rabbit fame, thought himself a rakish Jack of Knaves. Such a suave countenance should by no means go unheralded. He built himself up to be a legend in his own mind. “I am Legend”, he said, having heard that somewhere before. He made himself a hat of green felt with a snakeskin band and a feather stuck into it. “Hah! A feather in my cap! Always knew it!” he said, as he carefully fitted it and pulled it down over one eyebrow. Then, clapping his hands gleefully in front of his full length mirror, he gave his moustache a Dali twirl to complete the picture.

Just last night, he had had a dream in which a thing instructed him in the building of a contraption that would endow him with the freedom of flight. What is more, it suggested to Harvey that, if he embarked on his maiden flight at a certain hour on a certain night, he would gain the means to become The Power, and would rule over all the hamlet of Glynn, neatly nestled on the shady side of the mountain and down into the Valley of Dim.

As we know, Harvey was an excitable lad, and grandiose dreams such as this one do not happen all that often to us earthlings. “Yes. Yes!”, he said to himself. “I can build the machine. But what am I to do in the middle of some godforsaken night while putting around the rooftops of Glynn?” Three more days went by, and The Date was but a week away, when Harvey was favored with chapter two of the machine dream.

The marvellous contraption, if built correctly, would provide Harvey with more lift and hovering power than he would need, and, best of all, it would fly in absolute silence.

That was important, as you shall find out in a minute. The dream thing told Harvey that he was to build a small box of brass with a hinged lid that could be locked. He was to take this with him on the flight. “And, at three of the Wee” it said “Ye shall touch each tree. And then, ye shall light on each chimiNEY. Open ye box, collect a second of its smoke, see? Close fast the lock on the lid, then go ye to the next, ’til all is done. Aye, it is thirty and nine, hear me? I’ll tell ye more, the night before.”

Harvey went into Glynn in his finest outfit, feather in hat, smiling and saying Halloo to everyone he met. He collected all of the peculiar things he would need for his tinkering, and pedalled back home, pulling his little cart behind him. By Caturday’s Eve, all was ready, and Harvey indeed was surprised and excited because he had piloted his “Dragonflyer” on a short maiden flight. He went to bed early, without tea, for he knew he had to be alert and ready in the wee hours of the morning. Besides, and more importantly, a dream story was yet to be told.

¶n the chimney smokes of Glynn (his dream master said) dwelt the darkest secrets of every man and woman therein. Harvey’s box of brass would be the collector of those secrets, and he would hold The Power of their knowledge. He need only speak discretely to a few of the townsfolk. When it became clear that Harvey knew things, it would not be long before he could install himself as The Grandee of Glynn, or so he thought.

In the darkness of Caturday’s Eve, the flight of his Dragonflyer was true, and before dawnlight, Harvey’s deed was done. All was still, until the mutterings of thunder were heard. A seed of panic was planted in Harvey’s mind, and he set off homebound with haste. But, as we know, persons who have bad intentions seldom succeed. The dragon contraption flew as promised until the sizzling bolts of lightning shot their spears at the unfortunate pilot, and one could see his panicked progress in the strobelights of the storm.

All at once, a stray bolt struck the brass box! Harvey was stunned but not electrocuted, because of the thick gloves he had worn against the soot and heat of the chimneys. But the force of the bolt threw him and his box out of the craft, toppling them a hundred feet into a mound of hay bales by his barn. The dragon flew away, doing crazy pirouettes in the dawn sky.

Sore and disheveled, Harvey found the box and went into his house. The box was still locked. He set it on his kitchen table, then decided to go upstairs for a much needed rest (even though it was broad day).

That same morning, while Harvey was snoring upstairs, the people of Glynn were waking up a little later than they usually did. Their little children were, of course, up at their normal time, that being the crack of dawn, but they could not wake their snoozy parents until some time later. That was because something curious had happened during the night. For some reason, all of the Moms and Dads felt strangely light, as if a weight had been taken from their shoulders. They were happier than they had been for many a year. Of course, that was simply because not one of them could remember the secrets they once held, or the sins they might have committed. When they went out into the streets, they greeted neighbors they had not spoken to for a time because of remembered grudges that were now swept away.

As for Harvey, well… he smelled smoke, and then he began to feel very peculiar. Downstairs he went, to discover that the brass box had flipped its lid. Its secret smokes had inundated his house, and he had already breathed in too much of them for his own good. He ran for the door and threw it open, then the windows! Harvey slumped into his old livingroom chair and, if you were a little mouse or a fly on the wall, you would have seen his eyes bulge, his hands quiver, and his head shake back and forth. He muttered strange words that were like a foreign language, then ran out in his striped pyjamas.

It turned out that his flying machine had, after doing various accidental manoeuvers ,

fallen into the same pile of hay that had saved Harvey. Still shaking and muttering in his blue pyjamas, he got onto it and took flight into the wild blue yonder.

Harvey was never seen again, and Pandora rolled over in her grave.

Sequestered

Darlene and Dave,

they had a love.

On grandfathered land,

they built a house of modesty,

high under the evergreens.

Neighbours flocked to raise the roof.

Each brought shingles, cedar shakes

of secret colours, ’til unboxed.

The coffee, the tea, the hot chocolate.

The joy. The laughter. The promise,

in that snowy October.

First came Darlene’s gardens,

with care-woven roots.

Then, a son and daughter, a year apart.

Never the holiday they took.

Never did they want for other lands.

But the boy and the girl,

they went to good city schools,

and soon they had a hankering.

With their earned degrees, they wanted the world.

There were stoic farewells, in time.

The house of modesty had a change in its airs,

too many spaces in its purpose.

And Darlene plied her trade in the summer gardens,

trying to grow what might fill.

And Darlene took a room

and made tapestries of delicate beauty.

Quilts that had no rival.

And Dave took a room

and tied fishing flies

and made soldiers and cannons of molten metals

and hammered copper story scenes for the walls.

And they did go to a hidden summer lake

to swim and to collect things that drifted.

And even after their middle age

they skated on that lake,

sequestered in the snow.

On a summer, Darlene was kitchen-bound,

baking for a lakeside lunch.

She wondered at the change in the timbre of the riding mower.

Dave never left it running, she knew.

Rinsing her floured fingers,

she went out the back screen door to call him,

but her Dave had died. His heart.

~~~~~~~~~

These ten years now,

I have delivered Darlene’s groceries.

Waiting on her visitors from foreign lands,

she was soured to the world.

Took up with the smoke and with the drink.

Today, as I drive the muddy road,

I have a companion with me.

The nurse that will tend to my old friend.

The cedar shakes of the bowed roof

still show a checkerboard of colour,

even in this grey streaming rain.

I have always thought that each one was signatory

to a day in the lives of those two.

A smattering of their joys, their fights, their triumphs, their sadness.

Darlene had called this morning

to tell us not to knock.

To just come in the front door,

take off our wet boots.

She sits in the back living room now,

in a fluffed robe,

with her tobacco.

Sequestered from the gloom,

but part of it, too.

Tommy, can you hear me?

It wasn’t that long ago that he turned fifteen. We sat on the cold concrete of his front porch, watching the iffy clouds discuss a storm. I always sat downwind from him ’cause he didn’t like my smoke. That day, a brisk and cool crosswind hinted at summer’s end, and the sailing cloudbank made me think of angry giants.

When I first met Tommy, he was about nine years old. He’d been a handful for his parents ’cause in those days there were no “programs” or government assistance for kids with “developmental challenges”. Tommy was okay physically, but seemed muffled from what we think of as the real world. His folks had advertised for a caregiver, to be “available once or twice a week” so that they could at least have a little respite from that daunting task. I don’t see them as bad or lazy people, and I too would have needed some time away if he were mine. Anyway, there must not have been very many responses. They took me on, even though my sole qualification was that I had spent a couple of summers as a camp counsellor.

It was not without emotion that Jan and Barry Morgan left their son in the care of someone else for the first time, and I am sure they had their misgivings. I had brought two baseball mitts with me in case Tommy didn’t have one, and we were playing catch when they made ready to go. He dropped his mitt and ran to them crying. I came over and put my arm around his waist, while Jan tried to explain to him that they were going into town and would be back by four o’clock. Still he clung, so I took off my wristwatch and strapped it onto his skinny arm. “Hey, Tommy. That means we have lots of time to play catch. See the short hand on the watch? When it gets all the way around to the 4, Mom and Dad will be back. And if you get tired of catch, we’ll fly your kite.” I give the kid credit, for he let them go without too much more of a fuss, and we spent a pretty good afternoon.

You know, it shames me to say this. Whenever I have come across a person who was known as a “deaf mute”, I’ve been afraid. Afraid of not knowing how to communicate with them, or even whether or not I should try. I felt them to be unreachable or, worse, unreasonably aggressive because they were different. Maybe I even thought that they knew something that no one else did. Maybe I even thought that they needed something that I couldn’t give.

And I did think that Tommy was all of these things, for he was uncommunicative, if not plain stubborn. And yes, he was aggressive at times, punching me with his small fists when I tried to shake him out of a funk. But, gradually, I began to learn the language of his world. He did make sounds, and could call his Mom and Dad. The most curious thing was that he did not call them Mom or Dad. He called them Jan and Barry.

As my time with him grew longer, his parents came to put trust in me, and they made me feel as if I were part of their family. And, you see where this is going. I came to love Tommy as a son. Although he did not, or could not, respond to being addressed in an everyday manner, he knew how to tell you what he wanted or needed. He could even play us off against one another in order to get it. Yes, there were the times when he scared me and showed me my inadequacies. Times of long silences and of unexplainable aggression. Times that I thought he was grieving for someone or something that I knew nothing of.

On that cold fall day, just after his 15th birthday, with the looming of those colossal clouds, and my behind getting cold from the concrete steps, I said “Well, Tommy, let’s go in and make some tea”. Expecting no response, I gently took his hand to get him up. He pulled back, wanting me to stay with him. “Mike”, he said, with a long “M”. The first time in those six years. He then pointed to the blackening clouds and brought his index fingers to his eyebrows. He looked at me full in the face and smiled. Once more he pointed to the clouds and then, unmistakably, he traced the initials “T.M.” in the air.

Smiling even more broadly, he touched his temples and tapped them several times.

Excitedly now, it was he that pulled me by the hand, urgently wanting me to follow him. Follow him to the big old maple tree on the edge of their property. There had long been a hive there, and it was active with the bees wintering down. He ran ahead, even against my call, and started to climb. Fearing the worst, I yelled after him..”Tom! Tom! Stop!”

He straddled the limb just below the buzzing nest, laughing and tapping his forehead. I felt as if he was “seeing” things for the first time, and I couldn’t help feeling happy and a little proud. I called for him to come down and hugged him tightly, as he said my name one last time.

Passings

It’s a slow down zone, and, in today’s tiny town, a little girl with scabby knees dawdles along the sidewalk. Her chin and part of her white T shirt are stained dark purple from the grape popsicle she’s licking. As she passes a picket fence, she puts out a pudgy hand as the slats go by. She likes the soft suggestive sounds and the roughness of the old wood. The rhythmic ta-TAT-ta-TAT-ta-TAT as her small fingers brush along the boards.

Soon, the fence gives way to the clipped green lawn of the local Legion. Celia had first seen the rusty army tank from the swaddling blankets of her stroller. Mommy had taken her for an outing on the prelude to a winter’s day, some eight years ago. Today, she wants to climb up and sit on the gun turret, even though there’s a sign that says

Keep Off, and even though Mommy has said “don’t let me catch you”. Up and down the street she looks, then reaches for one of the fenders to hoist herself up….but it’s no good. All at once, she’s reminded that she’s late, she’s late, for a very important date. The oversize wristwatch, strapped to her wrist by Mom, tells her she had better get going. They’re going to see Aunt Daphne, and she has to get cleaned up and dressed up.

In a few minutes, Celia is climbing the steps to her front porch. Mommy is sitting there with her arms crossed, a bad sign. “What on earth were you doing?” Celia, covered in dirt, has a purple face and a runny nose into the mix. Oddly, as her Mom stands up, Celia just hugs her waist and says “It’s alright. It’s alright.” Mom takes her by the hand into the house. “Girl, it’s bath time, and God knows how I’m going to get that purple off of you.” Celia sticks out her tongue, which is also purple.

This day, as they ease into November, the darkness is coming on sooner, so Mom wants to get the drive over with before nightfall. When by herself, she is prone to speeding a little, but tonight she has Celia in the back seat (where she has always made her sit for safety reasons). As they pass the last traffic light in town and head onto the open road, a Police car happens to pull in behind them. She keeps, of course, to the speed limit, and the Officer keeps a respectful distance back. “Celia, keep your eyes open. We’re coming to the big curve. You might see some deer up there.” As they’re about to enter the wide curve, Mom notices a huge tandem trailer of logs approaching them, just straightening out from the corner. She slows down a little, out of instinct. Sometimes these big rigs stray over the centre line by a foot or two. At that exact moment, a car pulls out from behind him and floors it, trying to pass. Mom slams on the brakes, steers too sharply, and hits the steel guardrail. Their car catapults and rolls down a slope towards the lake.

Officer Remy had steered in the opposite direction and had hit the rock cut on the left.

As luck would have it, he had grazed it sidewise, but at considerable speed. His cruiser was a write off, but his injuries amounted to a sore shoulder and neck together with some broken ribs. He was able to summon help.

Celia wakes up in hospital with her Aunt Daphne sitting at her bedside. Celia has a plaster cast on one arm and one leg. Her vision is blurred, but she can tell that her Aunt has very red eyes. When Daphne sees that her niece is conscious, all she does is hug her tightly and cry as she has never cried before. Their lives have changed, and the future has turned as cold and as grey as the bleak November sky.

Gehenna

A word whispered by winter’s ghost

in last night’s dream of loss.

Gehenna

So foreign to this man,

it held a portent.

This evening,

as he sweeps winter’s leavings from his tilted deck,

Gehenna echos back to him in a latent sigh.

He and his Margie. Gone these two years.

The deep ravine behind their home.

Its choked and bubbling stream.

The shopping carts, beer bottles, stinking refuse, dirty mattresses.

Once, there were many cherries there.

Flashing, one night.

Yellow tape.

Hushed bystanders.

Part of a person had been found.

He and Margie had stayed in their own yard.

On a night in the spring of ’17, Margie didn’t come home from work.

Margie didn’t call.

Margie was never found.

Margie wasn’t heard from again.

The ghost of winter had a voice of chill.

Tonight, as it sighed the same syllables,

a thrill of knowing made him drop to his knees in the twilight.

Margie.

Gehenna.

***

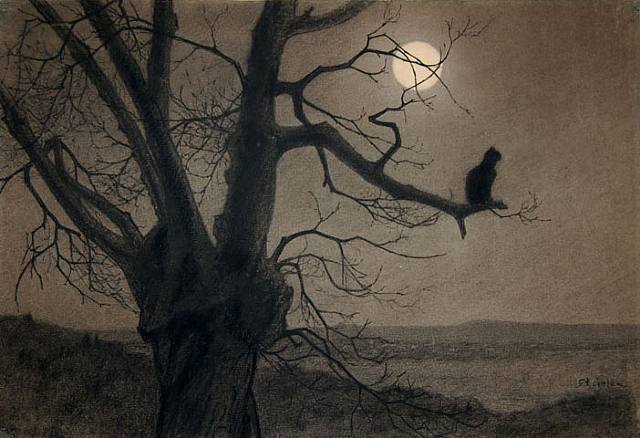

Art work by Theophile Steinlen – Chat au Claire de Lune (from Pinterest)

With this ring

This night, I am a sardine, riding the stuffed subway. The atmosphere is a mix of hot salami breath, boozy exhalations, overboard perfume, and the intrusiveness of freshly smoked weed. People pressing, gravelly coughs, wonky ringtones, shuffle shuffle shuffle. No place for the anxious or the introverted or the healthy. My brain buddy says to me, by way of consolation, There there. At least you aren’t in India. Or China, or London, or…. Yes, I have seen the photographs. People squished against glass doors, and professional train stuffers that won’t take no for an answer. In this, my lifelong town, we haven’t come to that pass yet.

Hey, if you pass out, at least you won’t fall.

We careen through tunnels of semi dark. On a curve, I am prodded by elbows and my foot is stepped upon by a hard heel. In the jostling, I can’t tell whose, and no one says sorry excuse me or anything of the like.

From my forced vantagepoint, I fix on a pair of female hands but I cannot see their owner. They rest upon her skirted lap, and, oddly, they don’t hold a phone. She moves them in peculiar ways for a young person, cupping one hand within the other and rubbing slowly back and forth as if in arthritic pain. Joining her hands, she then raises and lowers them in seeming prayer or supplication. Finally, she reaches into her pocket or purse, brings out a small circlet of paper, and slips it onto her ring finger. I see that it’s a cigar band and I chuckle to myself, having seen this sort of thing in the movies where the boyfriend asks the girl to marry him but can’t afford a ring.

She plays with it for a few seconds, turning it round and round, then takes it off, as if to put it away. She drops it on the floor, then quickly picks it up. I glimpse a head of long straight tawny hair, and her young face in profile. She sees me and I redden a bit, smiling sheepishly. Apparently conscious of an audience now, she stops fidgeting. One hand rests flat upon her knee, and the other is closed loosely in a fist.

With two more stops to go before I reach mine, I begin to sidle towards the doors, but stop for a moment as I draw close to her. She’s unaware, I think, because she has her head down and is toying with the ring again. Slips it back on once more, then looks straight ahead. She sees me, and gives a Mona Lisa smile. I feel like her decision’s been made, and I smile back.

The doors open and I push my way out onto the platform. I stop for a second, thinking.

Yeah, I knew it. I know it. This girl, who is now a woman, I have seen before. Her life of running away is no more, and I’m so happy. Yeah, I’m happy.

Fingers and toes

Every day, I get on the subway at the beginning of its route. About 45 minutes later, I am right downtown, three stops from the end. With any luck, it’s about 7:30 in the morning, and I have lots of time to get a Starbuck’s. After my day in the cubicle, I’ll be back in my parking lot by 5:00.

On this miscellaneous morning, Google says it’s gonna be a hot one. Already, at 6:45, it’s 25 Celsius. There are plenty of people waiting with me for the silver doors to open. There’s the whoosh of wind, the strange vacuum sensation, and the expected climax of chimes in C minor. It’s not unusual for the subway cars to have a few seats already occupied at this, the end of the northbound line. People one stop down the line will get on, just to have somewhere to sit on the southbound journey.

We all get on, and everyone finds a seat. Most are occupied, either with their phone, or with one of those crappy cups of coffee from the station’s vending machine. Straight across from me, next to the doors, a young girl sits. It’s a row of three seats, and no one has sat beside her. Without being obvious, I fall to studying her aspect and mannerisms. She wears a pair of lime green gym shorts and a grey zip up hoodie. It obscures her features to a degree, and her downcast gaze and unwashed hair leave just a runny nose and pouty lips showing out. She’s about thirteen, I think.

There are some odd things about her that pique my curiosity. She wears white socks and no shoes, not even flip-flops. In a pigeon-toed manner, she keeps crossing and uncrossing her feet, bending (and cracking) her toes unconsciously. She has no phone, or so I assume, but it’s her hands I’m focused on. Her fingernails are bitten to the quick, but what I see her do fascinates me, as if I have run across some accidental art. With each hand, she touches, in sequence, the tips of each finger to its member thumb, and then repeats as if part of a game. Then, the tips of all digits from both hands are brought together and flexed as if in a bellows. Tiring of this, she inscribes, with a forefinger, letters upon the palm of the opposite hand. I felt sure that she was spelling something out, and would have given much to read the message. At the last, and just before my stop, she meshes her fingers together and begins to twiddle her thumbs. I have heard the expression before, but have never seen someone actually do it.

As I get up to leave, she looks up for a second, and I see keen blue eyes with lashes stuck together as from stale tears. I step off, trying to think about Starbucks.

This muggy afternoon, I catch my 4:15 to head home. But you have guessed already. Serendipity has shone upon the scene, and this girl sits a few seats down from me. Something tells me she will be there when I reach my destination. In my briefcase I have a pastry, wrapped in plastic, that I bought for the trip home. I stand up nonchalantly, as if getting off at the next stop, look at the subway map, then sit down beside her. She shrinks away a bit, perhaps thinking that I am that weirdo she has been told about.

“I saw you here this morning, and here you are again. Are you okay?” She says nothing, then moves her feet from the floor up to her seat, hugging her knees. “Where do you live?” I do not want to go home she says. I had expected something a little less formal, like “I don’t wanna go home”. “Here…are you hungry?” I offer the pastry to her and she takes it, quickly eating it with her head turned. They drink and they take drugs and they buy things, but not for me. They tell me to hide when someone knocks on the door.

“Look, take this money. Is there a place you can stay tonight?” My friend’s dad has a hotel. He makes her work at the desk sometimes. She could let me stay. He would not know.

I pencil my number on the back of a business card. “Call this number if you need help.

What is your name?”

Layla.

The next day, as I’m eating my substitute pastry, my phone rings. Unknown number.

At the gate

I bring cats to Restful Acres. I guess they’re called therapy animals now.

I’m a widower, in my 50’s, and fortunate enough to have time on my hands. In the last few years, the faces here have come and gone, and some have become friends to me. My old Mum was a mainstay here, but she passed just over a year ago.

There’s an old fellow that came here about two months back. I don’t know his circumstances, but I can tell you that I’ve never seen him have any company. His name is George, and each time I come, I bring The Captain with me to try and cheer him a little.

Captain is a fat old grey tabby with a bent tail and only one eye. I “rescued” him from a sordid life on the streets, although I think he mainly resents being domesticated. But, he is gentle enough with people and affectionate to a degree.

When I come, George is always in his big rocking chair. It’s an antique, and no doubt belongs to him or to his family. Its ornate woodwork and plush upholstery seem at one with his ever-present cardigans of cashmere and their buttons of bone. Today’s colour is a pale mauve. Yesterday’s was pastel green. I think he may have one for each day of the week.

George does not speak. Indeed, he has never made a sound in my presence, save for the occasional and unavoidable escape of gas. I have learned that he has his own private nurse, and that he must have come from a well established family, for he is always impeccably groomed. No hair out of place, moustache trimmed just so, manicured hands, cologne in just the right amount. The nurse tells me that he is a veteran of two wars, and that he has not spoken since his arrival. She encouraged me to come visit him with the cat, as nothing else had seemed to reach him.

The first two visits I made did not evoke a response. I made no attempt to speak to him, save to ask him if he would like to hold the Captain. His startling eyes stared at a point a little above him and to the right, as if in contemplation of a thing terrible or celestial, and he seemed not to blink. The offer of the cat had no effect upon him, even if I set it gently in his lap. The third time I came, I noticed that while his big hands rested palm down on the flat of the rocker’s arms, his right index finger was keeping up a steady beat upon the wooden surface. Like a metronome, it never lost or gained time. After watching this for a spell, I realized that each beat was exactly one second. The clock on the wall confirmed this.

I will say that nine minutes had elapsed with his steady tapping when he stopped abruptly and turned his hands palm up. His stare did not change, but he leaned forward slightly and brought his hands together. I knew this was Captain’s moment, and I placed him gently into George’s hands. He leaned back, gathered the cat to his chest, and for the first time guided his gaze away from its singular focus. George was now present, at least for the moment, as he bent his head to study the purring animal he was stroking. I could not see his face clearly, but I fancied I saw a slight crinkling of that grey moustache as a smile of serenity spread. As he raised his face, his eyes were closed and wet with tears. His bottom lip quivered before he regained some control, and then he handed Captain back to me. I offered him a handkerchief. He gave the smallest nod, and took it to wipe his eyes.

Two deep breaths he took, then raised his chin once more, his eyes moving back to that point inscrutable. I then felt like an interloper, a voyeur, because I could see quite clearly that George was reliving something. Terror, shame, blame, courage, and things unholy were shown out in the rendering of his spirit. Now I knew that George had only been waiting. Waiting at the gate.